The following is a guest post by Christopher Lee and originally appeared on his blog. Christopher is currently in the Ruby-003 class at The Flatiron School. You can follow him on Twitter here.

During my second week of learning how to code at the Flatiron School, we were given the Towers of Hanoi problem to apply our new found knowledge of recursion. Needless to say, it was really challenging. From my experience, what makes Towers of Hanoi difficult is two-fold. First, recognizing the pattern was far from obvious (I spent hours painstakingly moving paper discs around). Second, once you have an algorithm to solve the problem, it’s not exactly clear how the computer executes the recursion calls. This post is intended to help shed light on the latter.

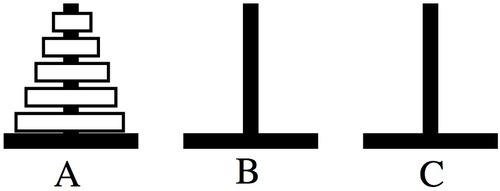

For those not familiar with the rules, there are three pegs (source, spare, and destination). The goal is to move all of the discs from the source peg to the destination peg one at a time without ever having a larger disc on top of a smaller disc. As shown in the diagram below, let’s assume that the ‘A’ peg is the source peg, ‘B’ peg is the spare peg, and the ‘C’ peg is the destination peg.

Source: Brandeis University, CS Department

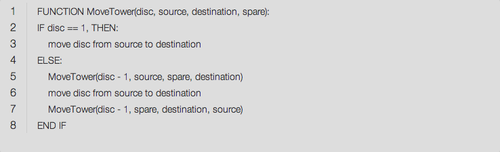

Conceptually, we can break the problem down into a few moves. First, we need to move n-1 discs to the spare disc. Then, we are free to move the largest disc (nth disc) to the destination peg. Once we have the largest disc on the destination peg, we need to move the original n-1 discs (now on the spare peg) to the destination peg. With this logic, we can define a function that looks like the algorithm in the figure below.

Source: Carnegie Mellon, CS Department

However, you will notice that we are calling the original function again whenever we call the function with a number of discs greater than zero. This makes sense since moving n-1 discs all together is not a legal move. Thus, the same function is called again with n-1 discs, and the pattern continues until we reach the base case where the number of discs is equal to one and the base case solution executes.

The above pattern is both what makes recursion powerful and hard to understand. Given the repetition of the same logic, it’s helpful to be able to make recursive function calls as it enables us to have a concise solution. However, tracing the execution becomes difficult given the nested nature of the function calls.

As we step through each level of recursion, it’s important to realize that the interpreter executes the code in a linear, top-down manner. With each recursive function call, the computer attempts to find a solution to the smaller instance before returning to its original place in the program. This is why large recursive calls lead to stack overflow.

Returning to the algorithm, you may have already noticed that there is an additional layer of complexity. With each additional recursion call, the “source, spare, and destination” pegs change because the arguments to the function call switch in comparison to the original function. So, in the first line of the else statement, the original spare peg becomes the new destination peg, and the original destination peg becomes the new spare peg. For the last line of the else statement, the original spare peg becomes the new source peg, and the original source peg becomes the new spare peg.

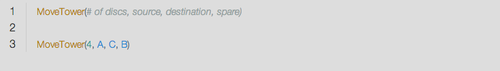

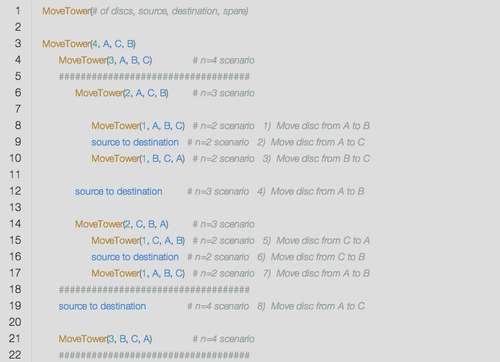

With that in mind, let’s step through each level of execution. Given 4 discs, we call the MoveTower function the first time with 4 discs.

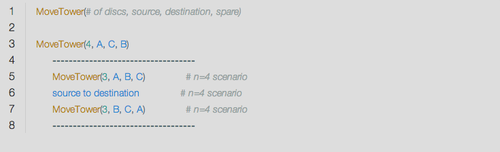

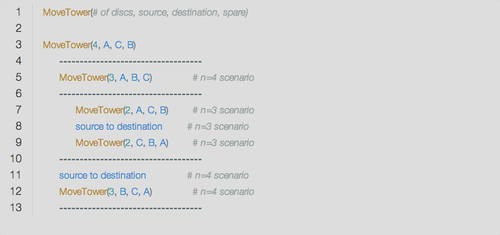

Based on the function definition, we know that the condition in the if statement evaluates to false and consequently, does not run. The interpreter then moves to execute the body of the else statement (figure below), which we’ll call the n=4 scenario to keep track of where we are in the program (i.e. we are within the body of the else statement for the MoveTower function with 4 discs).

Notice that the algorithm swaps the original destination peg with the original spare peg. So, the first line of the else statement calls the same MoveTower function with n-1 discs and the pegs switched. Since the number of discs is still not equal to one, the MoveTower function is called again, which results in another else statement. Notice that each additional function call becomes nested within the previous function. This is because the interpreter needs to resolve the function call before it can execute the next command.

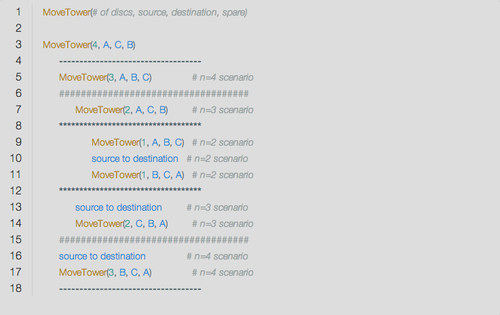

Next, we see that the number of discs is still not equal to one, so the interpreter calls the same MoveTower function with n-1 discs and the pegs switched again.

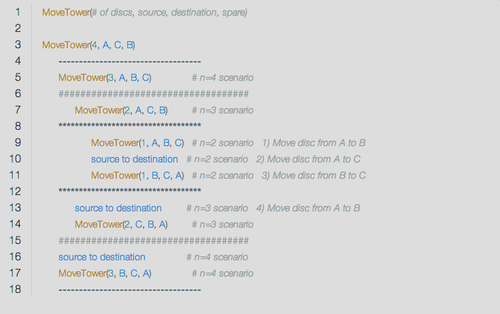

Finally, the if statement of the MoveTower function evaluates to true, and the interpreter moves one disc from source to destination (A peg to the B peg). Now that the interpreter has received an answer, it then moves on to execute the next command. It’s important to remember that once the interpreter resolves the function call it returns to its previous place in the program (in this case within the else statement of the n=2 scenario). So, the source to destination command results in one disc moving from A to C. Then, it finishes the else statement by calling MoveTower again with one disc which results in a disc moving from B to C. Once completing those three steps, the interpreter has completed the MoveTower(2, A, C, B) function call. It then returns to its previous place, which was within the else statement of the n=3 scenario. Next, the interpreter completes the source to destination command, which moves a disc from A to B.

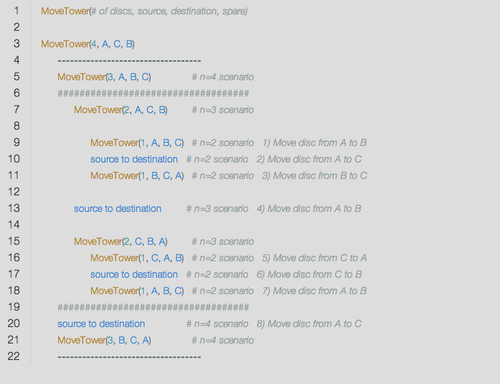

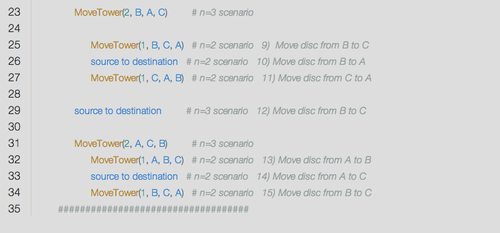

Continuing with the top down execution, the interpreter then reaches the MoveTower(2, C, B, A) command. As we previously saw, MoveTower is called again because n is not equal to one. The result is similar to the previous instance when MoveTower had two discs, however the pegs have switched around yet again.

Once completing the MoveTower(2, C, B, A) function, you can see that we actually just completed the first line of the else statement from within the n=4 scenario. So, the interpreter then runs the middle statement (i.e. source to destination) and moves a disc from A to C. Finally, notice that the next command is to execute MoveTower(3, B, C, A), which results in yet another series of recursive calls similar to the first time MoveTower was called with 3 discs.

After 15 steps, we finally reach the end of the program. Since the solution accepts any number of discs, you can now see why the execution increases exponentially with each additional disc added. Thanks for reading, and I hope this post helped you understand how recursion works within the context of the Towers of Hanoi problem.

I also wanted to thank Spencer, Suneel, and Rebecca for helping me understand the solution. I owe you guys a drink 🙂

Written byFLATIRON SCHOOL

Make yourself useful.