This article originally appeared on Course Report—head there for the full post!

As a future coding bootcamp-er, you’re most likely new to tech and full of questions—and misconceptions—about what learning to code at a bootcamp and being a developer really entails. With over 1,000 Flatiron School grads making their way through the tech world, Flatiron’s team has access to a lot of developers who are eager to share what they’ve learned through their countless hours of mistakes and breakthroughs, whether they’re new to the field themselves or seasoned tech professionals.

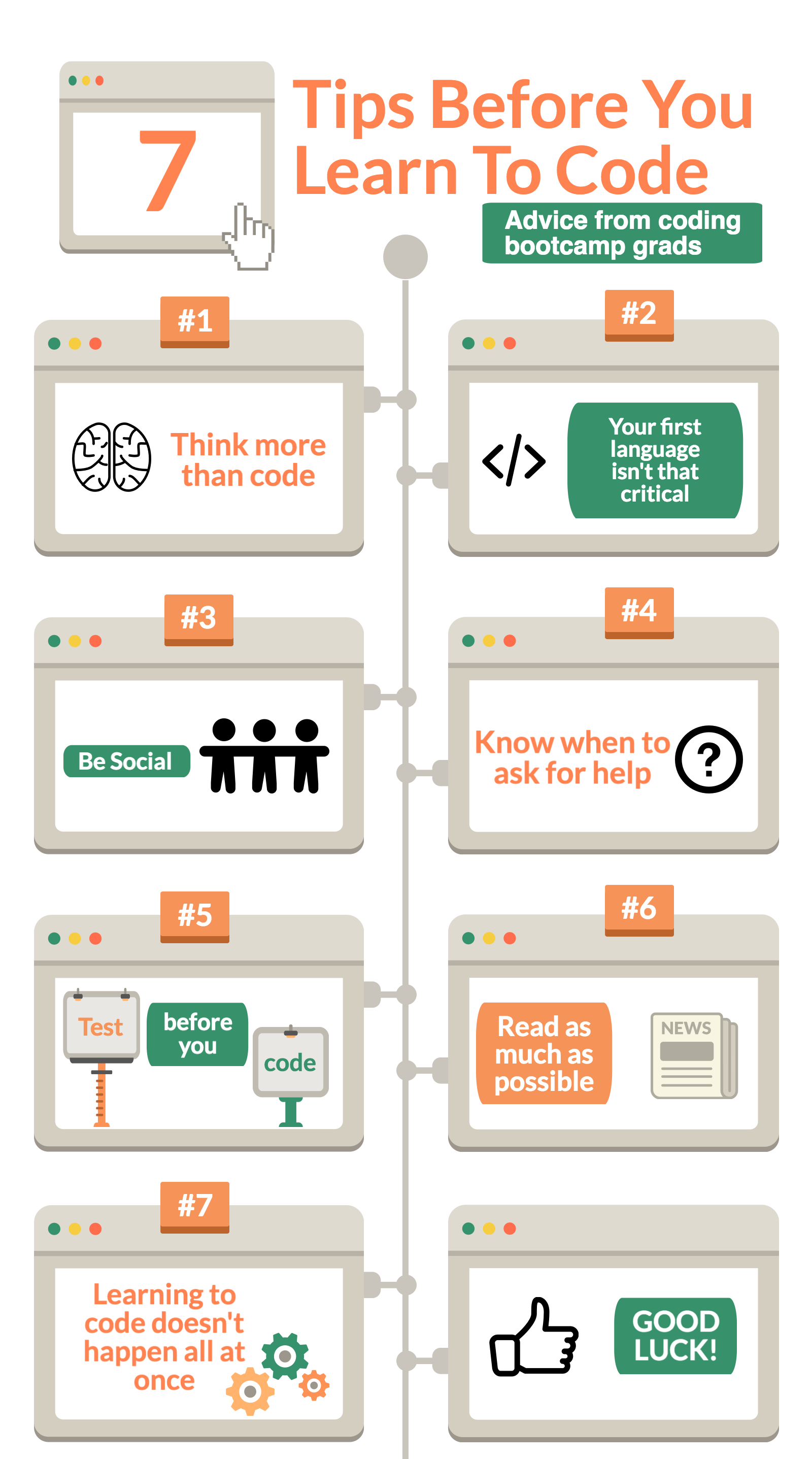

Here are a few tips and truths about learning how to code and starting your life as a developer that the developers we spoke to wished they knew before they started their own paths to programming:

1. Think more than code.

Ian Candy, Developer and Instructor at Flatiron School: “When I pictured what it would be like to be a developer, I imagined someone writing tons of code, their fingers flying away at the keyboard like they’re trying to hack into the Matrix—the faster you could type, the better the programmer you were. But after joining the team, what I found is that the better developers were actually the ones who spent a lot of time in thought—not actually writing anything but rather thinking out problems. As a team, a lot of times we’ll spend five to ten minutes just talking about what a method should be named to accurately reflect what it’s doing, or an hour discussing how classes are set up and how they interact with each other.

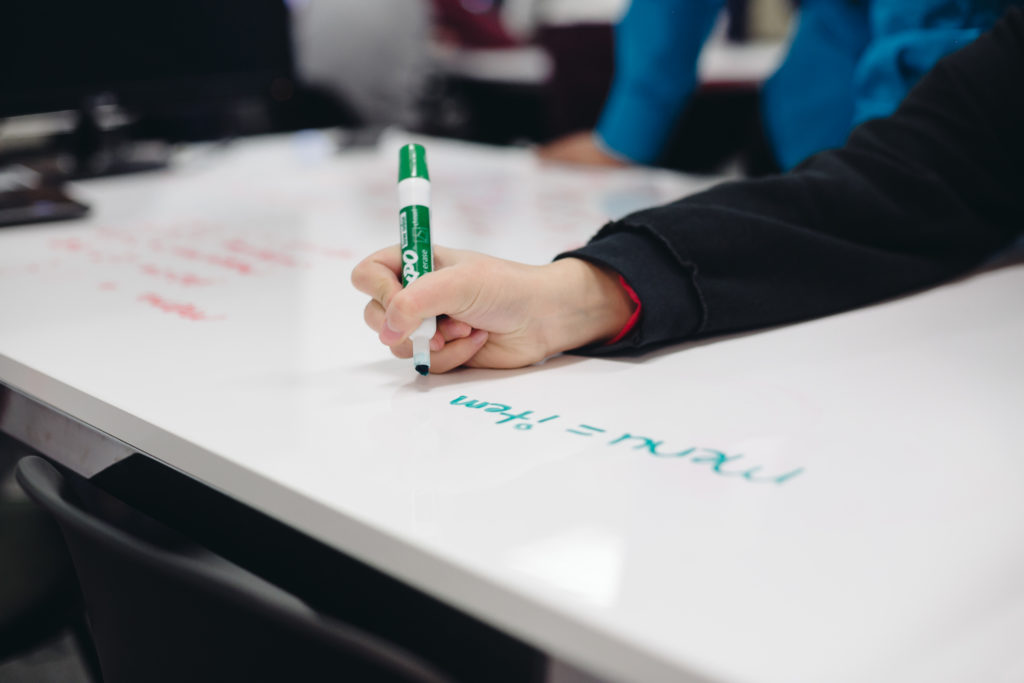

I have a specific memory of talking through a problem with a senior developer. I expected it to be a simple thing—I just had to add a table to a database. When I told the senior developer what I was thinking, he paused and said, ‘We need a whiteboard. We need more brain space.’ And as soon as we started writing down the problem and how everything worked, I immediately realized it was much more complicated than I had imagined. When I got the chance to step back and think through the problem, it looked completely different. Taking the time to think allowed me to make sure what I was planning was correct and that the code I ended up writing was more stable.”

2. Your first language choice isn’t that critical—it’s more important to start learning.

Sarah Alder, Front-end Engineer at YouNow & Flatiron School alumna: “Learning any language gives you a point of reference to learn another. When I started coding in 2015, I got accustomed to the object-oriented programming via Ruby, but now I use Javascript on a daily basis, which, though still object-oriented, has functional elements to learn. I’m sure I’ve learned JavaScript much quicker post-Ruby than I would have pre-Ruby. You can think of it like learning a natural, human language. Learning Dutch is much simpler if you already know German.

That said, I recommend starting with, a higher-level language like Ruby as opposed to a lower level language, like C, which is far less semantically rich. If C is like speaking in grunts and hand gestures, Ruby is like speaking in song and idiom. Those grunts matter! But, if you’re just starting out, a higher level language will give you more momentum. Coding is difficult enough to start. You should definitely not spend months self-flagellating in a cold dark windowless room learning machine code.”

Avi Flombaum, Co-Founder & Dean of Flatiron School: “Nothing will ever replace the basics. Beginners often try to keep up with technology in the same way that advanced programmers do. But all the languages are the same when you’re a beginner; it shouldn’t be a priority to use all the newest, hottest tools when you’re starting out.

If you’re really good at one language and you can use it to build amazing things, no one is going to care what language you used to make them. Beginners shouldn’t care about the languages they’re using. They should care that their chosen language matches their goals, if they’re getting expertise and depth and in it — and, of course, if they love using it.”

3. Be social.

Ian Candy: “I had imagined programming as a lonely, solitary journey where you alone have a problem and it’s your responsibility to solve it. But I’ve seen that the best developers on my team spend a lot of time interacting with other people, getting other opinions and perspectives. They’re social butterflies, going around pollinating other parts of the code base with different ideas.

We also spend a lot of time pair-programming, one person driving/writing the code, another navigating, steering them to a solution. We design ideas and plan out what the implementation will look like together.”

Avi Flombaum: “Always put yourself out there. Talk to the programmers you admire—even beyond the ones on your team. Even the super famous ones can be surprisingly accessible. As I taught myself to code, I’d go to conferences and stop my favorite programmers in the hall, or I’d write a blog post I was proud of and email it to them. Most of the time, they were incredibly generous. They’d help me promote the article, and I’d get really valuable feedback.

A lot of beginners are afraid to just reach out to great programmers, but they shouldn’t be. In my experience, almost everyone I contacted was supportive. And because I reached out, programmers I really admired offered to have lunch with me and even tweeted about my blog posts. Every piece of positive, constructive feedback I received made the times I had to hear something hard, or nothing at all, absolutely worth it.”

4. There are times to bang your head against the wall, and then there are times to ask for help.

Sarah Alder: “As with most things, you learn to code by doing it. If every time you get stuck, you immediately ask your brilliant, cool, and helpful friend Lisa for help, you are doing yourself a disservice. Depending on the complexity of the problem, you should give yourself a time limit for actively trying to solve it. If you’re struggling with something like simple string manipulation, give it 30 minutes before posting to Stack Overflow or asking your friend. If the problem is more complex, your limit may be a few hours.

When you’re first learning, you will benefit from asking questions when you max out your time limit. Once you’ve grinded on something simple for an hour, it’s obvious that critical coding thought habits are still too far out of your wheelhouse for you to be ‘productively stuck.’”

Ian Candy: “As an instructor, I had spent a ton of time preaching the philosophy of ‘look it up first.’ When you don’t know something, you have such a vast array of online resources to turn to: Google, Stack Overflow, etc. When I first joined the engineering team, I didn’t take my own advice. It took a while for me to get familiar with the code base—the app I’m working on is larger than anything I’d seen before with lots of different patterns built into it. Somehow I had this idea that all the answers would be there in the code base. I thought, whatever problem I was working on, there would be another example of something similar to turn to that would guide me. So for my first few months on the team, I was reading through a lot of existing code, trying to implement similar versions of what had been done there before.

But as the problems I worked on became more unique and there weren’t examples in the code base to look at, I had to turn to outside resources. My gut reaction was to say to the person next to me, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing! Help me with this!’ Then I remembered my old friend Google and started practicing what I preached as an instructor. There are so many answers, ideas, and opinions freely available out there. Even if there’s a problem I haven’t solved before, I can look outside our code base and find someone somewhere who has had a similar issue and at least get some information about it.”

Tracy Lum, Developer at Flatiron School: “It’s more than acceptable not to know everything, and not knowing everything doesn’t make you stupid. This took me way longer to believe than I’m willing to admit. When you’re approaching a massive codebase for the first time, a codebase potentially filled with legacy code and bugs, of course you’re not going to understand it immediately. Do yourself a favor and ask questions up front. I wouldn’t ask the same ones over and over again, but do your best to poke around and ask when necessary. Spread your questions among different teammates too if that helps. Just because something is in the codebase doesn’t mean it’s right. So again, be sure to ask if something seems confusing or strange. Plus, a lot of more senior devs (well, at least the ones on my team — you all rock) will patiently explain something with expertise and kindness.”

5. Test before you code.

Ian Candy: “If you read any guide on testing your code, it’ll say write your tests first, then write your code. I ignored this advice. I thought writing tests first made me slower and I didn’t want to reduce my speed. I wanted to get features out the door. It felt easier to just get something working and worry about tests later. Unfortunately, this makes writing tests really hard, not fun, and you don’t spend enough time doing it.

In truth, I just needed more practice at it. I wish I had given myself a chance to work on that. Give yourself time to practice things you need improvement on. Don’t ignore them for the sake of productivity. Keep in mind, when you start as a junior developer, your employer won’t expect you to be best at everything (if you were, you wouldn’t be a junior developer, you’d be a senior developer). So look for opportunities to learn and improve even if it momentarily slows you down.”

6. Read as much as you can—even if you don’t understand it.

Tracy Lum: “Read every code-related thing you can get your hands on. Books, blogs, news, documentation, source code — read it all and absorb as much as possible. You may not understand all of it the first time around, and that’s okay. You’re a beginner, and as you get used to your new career, you’ll be able to flip back, review it, and parse more. What you need now is a foundation or framework for understanding. For Rubyists, I recommend starting with Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby by Sandi Metz as well as Design Patterns in Ruby by Russ Olsen. They’re both foundational texts that’ll help you not only get the hang of writing quality software but also aid you in deciphering the code that the rest of your teammates have written.”

7. Learning to program doesn’t happen all at once.

Avi Flombaum: “Learning how to code isn’t going to be a constant, continuous accumulation of understanding. It’s going to be an S-curve, with troughs of not really getting it punctuated by massive increases in efficiency. You just have to be diligent and get through the troughs because this is going to keep happening throughout your career. Remind yourself that if you keep going, it’s going to make sense eventually.”

Now you’re armed with the knowledge that these developers wished they had before learning how to code and starting their programming jobs! Ready to begin the process yourself? Try out Flatiron School’s online Bootcamp Prep course.

Written byJOSH HIRSHFELD

Content Marketing Manager, Flatiron School